a love letter to novels

we would all benefit from regarding novels as art forms

If we read the new masterpiece of a man of genius, we are delighted to find in it those reflections of ours that we despised, joys and sorrows which we had repressed, a whole world of feeling we had scorned, and whose value the book in which we discover them suddenly teaches us.

— Marcel Proust

The novel is a living art form that has the power to expand our inner worlds and facilitate the co-creation of our outer worlds. I believe this wholeheartedly.

Living art form. What do I mean by that? Art form, because a novel’s creation demands imagination, flourishes with skill, and reveals truths about life. Living, because a novel is not fixed at the time of its creation—it evolves with each reader, critic, and shift in societal norms.

I often find myself in awe of the seemingly magical process that goes into bringing a novel to life.1 Sally Rooney will say things about her characters like “he walked into my brain,” and “[her voice was] the first voice that came to the page for me,” and “I was intrigued by them, I liked being with them on the page.” She considers herself a passive observer of her characters, quietly following their conversations and inner monologues. Her role is to follow where her characters lead and write down their stories. “I get very into character, and I inhabit that consciousness,” she says in an interview with the New York Times about her latest novel, Intermezzo. “That allows me to write about what it is that the character is undergoing.” Her readers tend to believe there is a relationship between Rooney’s life and the fiction she writes, but she insists that she is separate from her characters, going so far as to wonder why they are interested in the same philosophical, ideological, and interpersonal questions she is. Rooney seems to believe that she is not simply the creator of these characters, but their messenger.

This creative process—which, as I understand it, is somewhat externalized from the self—is surprisingly common among authors of fiction. Are they creating from themselves, or channeling a force greater than them? Keith Johnstone, a pioneer of improv theatre, writes about artists: “We have an idea that art is self-expression—which historically is weird. An artist used to be seen as a medium through which something else operated.”

This must be what Ottessa Moshfegh is describing when she says her writing process involves listening very carefully to a higher voice outside her own consciousness. To bring her mysterious titular character McGlue to life, Moshfegh placed a mirror behind her writing desk so she could assume his postures and expressions. “That’s actually a really important part of the process, because McGlue as a personality was really mysterious to me,” she recalls in an interview with CCCB. “I had to physically imagine being him in order to understand how he might talk or what his attitude would have been.” Her inhabiting of McGlue—a drunk, brain-damaged man in denial—was so all-consuming that she herself overlooked certain truths about him that her editors noticed before she did.

In another interview, Moshfegh says, “McGlue was really a creative act of writing through spiritual possession. I wasn’t intellectualizing, I wasn’t thinking about plot. McGlue came out of me like some magical demon. And when that was over, it was like, ‘Oh, thank God.’” But unlike Rooney, Moshfegh admits that there is a relationship between her life and her art; one influences the other, affecting her story, shifting her personality, sometimes even making her temporarily a little insane, like in the case of writing My Year of Rest and Relaxation.

E. M. Forster also seems to regard his characters as creations with their own minds, operating outside his control. In a 1953 interview with The Paris Review, he talks about how his characters often change the course of his story. (He generalizes this experience to all authors, but this is not every author’s experience. A little over a decade later, also in an interview with The Paris Review, Vladimir Nabokov responds to this claim with mockery: “It was not [Forster] who fathered that trite little whimsy about characters getting out of hand; it is as old as the quills. My characters are galley slaves.”)

Clearly, some stories insist on being told—perhaps to illuminate aspects of life that society prefers to ignore or to help an author resolve an inner conflict—and writers, from Rooney to Forster, are answering that call. This is, in part, what I mean when I say the novel is living. Sometimes, I like to imagine that the life of a singular novel can be as rich and complex as one’s own, from how it was born and sustained to its impact on those who interact with it and the world.2

When read at the right time, a novel really can change you, the way the kindness of a stranger might alter the course of your day or the words of a mentor might shift your perception of a problem you thought was impossible to solve. Many people will pick up a book during a dark period in their lives and emerge from their reading experience transformed. For example, the emotions and events depicted in a novel might help you realize you’re not alone, as famously noted by James Baldwin:

You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was Dostoevsky and Dickens who taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who ever had been alive. Only if we face these open wounds in ourselves can we understand them in other people. An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian.

You might find that an author has described an emotion or experience you’ve always felt but not been able to articulate nearly as well or at all. When this happens to me, I can’t help but excitedly scream yes! exactly! in my head while reading, like when Gabriel García Márquez wrote in Love in the Time of Cholera, “Human beings are not born once and for all on the day their mothers give birth to them—life obliges them over and over again to give birth to themselves.” This idea, that life repeatedly pushes you to create and recreate yourself, instantly stuck with me and imbued itself into all my experiences; without realizing it, I wrote about it during a particularly challenging time in my life over a year later.

French novelist Marcel Proust said the “number of human types is so restricted that we must constantly, wherever we may be, have the pleasure of seeing people we know.” This might be true in paintings and movies, but especially in stories. While reading, you might encounter a character who is so similar to someone you know in real life that it shakes you a bit—especially when the novel is written centuries before yours. I was so struck by the familiarity of Gustave Flaubert’s side character Monsieur Homais in Madame Bovary, published in France in 1856, that I instinctively reorganized all my perceptions of this type of person into perhaps something more whole, forgiving, accurate. Homais, a local pharmacist, is not exactly a likable character. He is materialistic, selfish, and self-absorbed, comfortably leveraging deceit as a means for his ambition and social climbing. Unprompted, he will launch into antagonistic monologues about the virtues of rationalism and science at the expense of religion, often using cliches and jargon he does not fully understand. He is earnest in his irritating habits; he simply cannot help himself. Maybe this is why I could not help but love how awful and annoying he was as a character. How many Monsieur Homaises do we know in our lives? Every time he appeared on the page, he irritated his fellow characters but absolutely delighted me. In a strange way, he helped me see this type of person, the smug hyper-rationalist, with a little more compassion and understanding. Homais was never satisfied with his life and was always the butt of every joke. He relied on these tactics to feel more in control of his life, more important than he actually was. Is this how the Homaises in my life feel?

The depictions of events and characters in novels are fictitious only to a certain extent. In his book How Proust Can Change Your Life, Alain de Botton reminds us that such imagined experiences expand our understanding of human behavior, especially our own: “After we have childishly picked a fight with a lover who had looked distracted throughout dinner, there is relief in hearing Proust’s narrator admit to us that ‘as soon as I found Albertine not being nice to me, instead of telling her I was sad, I became nasty,’ and revealing that ‘I never expressed a desire to break up with her except when I was unable to do without her,’ after which our own romantic antics might seem less like those of a perverse platypus.”

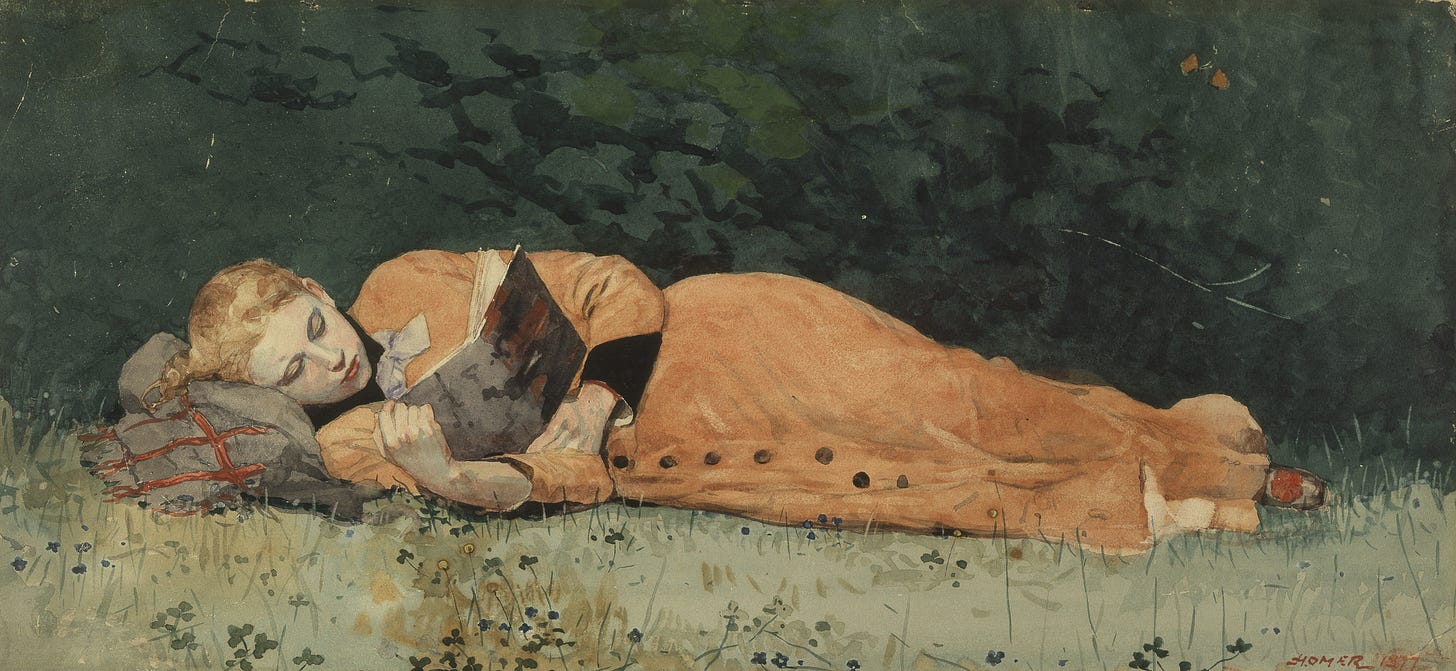

But I want to reiterate: timing is crucial. It doesn’t matter how well-written or revered a book might be; you have to read it at the right time for it to truly change you. I’ve yet to figure out how exactly someone determines the right time to read a book, but I think it’s intuition; you just have to feel it out. Sometimes a book will sit on my shelf for years, provoking feelings of guilt every time I look at it, and then one day I’ll find myself suddenly interested in getting to know it. I’ll pick it up and start flipping through it while hovering near my library, in case I need to put it back on the shelf. A word or a phrase might catch my eye, and I’ll take it to my couch, get cozy, and start reading. Suddenly, I find myself overwhelmed with the feeling that this book was written solely for me and my unique needs at that exact moment. If I had tried reading the book earlier, it might not have done much for me. In fact, if I sense that a book is not right for my current moment, despite being objectively good, I’ll stop reading and save it for later, as I’m currently doing with Toni Morrison’s Beloved.

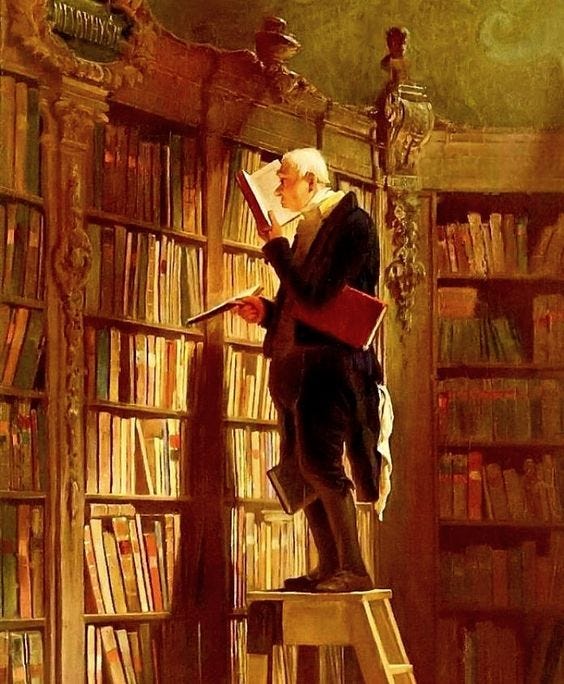

Having a personal library with several unread books—or regularly visiting a bookstore or public library—is partly what allows someone to choose the right book at the right time. Visiting a bookstore or perusing my library several times a week has become a ritual for me. The regular exposure and accessibility to a wide range of books help me develop my personal taste and become attuned to my current needs and preferences. For more than a year, I would walk into a bookstore and see Palestinian writer Yasmin Zaher’s debut novel, The Coin, wondering if I should read it. It sounded exactly like the kind of book I would like, but I wasn’t in a rush to buy it. One day, I walked into a bookstore intending to get a specific book, but as soon as I saw The Coin, I felt an urgent need to read it. I bought it without hesitation and read it in a few days; it quickly became one of my favorite reads of 2025. It made me so uncomfortable and elicited such disgust within me that I would regularly have to put the novel down and pace around my apartment before picking it up again.

Once again, the main character is not very likable. She is a rich Palestinian woman living in New York City, where she teaches underprivileged boys in ethically questionable ways, falls into a Birkin reselling scheme, and develops an obsession with cleanliness that brings her to (and sometimes over) the edge of insanity. In bringing her novel to life, Zaher brought parts of her self to life as well: “After seven years of being inside this novel, I think I’m a lot less clean than I used to be, and I also care about fashion a lot less. In a way it sort of healed me of my own obsessions.” Many might go into The Coin expecting the narrator, a Palestinian woman, to be the perfect victim, but Zaher finds that boring: “I’m always attracted to novels that bring me closer to my bad, secret fantasies, my repressed bad qualities. I think it’s because reading is engaging in fantasy, and writing is also engaging in fantasy, so it’s an exploration of parts of us that we cannot live in real life.”

I think this is what Proust meant when he described the novel as an optical instrument that allows a reader to read his own self. Everything that exists in the world exists within ourselves as well—the good and the bad. When we are so intimate with a character who flagrantly exhibits the “bad” parts of ourselves that we turn a blind eye to, we begin to understand ourselves a little more (assuming we can get over the extreme discomfort the novel might cause us). For Alain de Botton, reading a book causes our mind to be like “a radar newly attuned to pick[ing] up certain objects floating through consciousness; the effect will be like bringing a radio into a room that we had thought silent, and realizing that the silence only existed at a particular frequency and that all along we in fact shared the room with waves of sound coming in from a Ukranian station or the nighttime chatter of a minicab firm . . . The book will have sensitized us, stimulated our dormant antennae by evidence of its own developed sensitivity.”

Perhaps my favorite thing about novels, though, is their ability to facilitate conversations between your past, current, and future selves through rereads and margin notes. This is what I discovered when rereading my favorite novel of all time, Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi, for the third time in my life: “When I reread the novel for the first time in more than seven years, I felt like I was reconnecting with an old friend—one with whom my relationship had changed, but not my affection or comfort. That old friend, it seemed, was my past self. I was in a silent dialogue with this prior version of me, gently renegotiating many of the beliefs she held because of this novel. The process was unexpectedly therapeutic.” It’s similar to rereading old journal entries you wrote, except this time there’s a third party involved: the author. By making notes in the book’s margins, you are confronting your current thoughts, leaving bits of your current self for your future self to engage with, and addressing the book’s author—whose work ceases to be the author’s own once it’s released into the world. The book is not static, not merely an object: every reader, critic, essay, discussion, film adaptation—even simply the passage of time alone—shapes the book, expanding it and changing its meaning.

In her interview with Hernan Diaz, author of Trust (which I have not yet read), Dua Lipa asks a question about the novel that literally stuns Diaz: “Can I take a moment to thank you for this question? I have been on the road for a couple of years now, and I feel that I’ve heard every possible question in any possible incarnation, and this is so new and fresh and clever and I’m so grateful. And you know what, I had never quite thought of it that way myself. You’re right.” Like Moshfegh’s editors, who saw qualities in her character McGlue that she missed, Dua Lipa understood something in Diaz’s novel that he had not considered until confronted with it.

For James Wood, author of How Fiction Works, reading offers us more than just the opportunity to converse with ourselves and authors over time; it can help us understand the course of our lives. “Fiction ideally offers us a power we tend to lack in our own lives: to reflect on the form and direction of our existence; to see the birth, development, and end of a completed life. The novel provides us with the religious power to see beginnings and endings.” When I see parts of myself in a cowardly character, I can use their experiences to envision what shape my life might take if I continue down this path. When I get to act as a third-party observer of a harmful relationship depicted in a novel, I gain new perspectives on similar relationships in my life. When I read how a character dictates the story of his or her life, I am given the tools to dictate the story of my own life; stories are, after all, how we make sense of our lives.

The power of the novel is not limited to the individual sphere. Ayn Rand’s work has had significant cultural and political impacts on the US, affecting Americans’ daily lives whether or not they’ve read (or agree with) The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged. Shakespeare’s work pushed the limits of the English language, introducing more than a thousand words and phrases—many of which we still use today. George Orwell’s 1984 remains inextricable from how we think about surveillance and propaganda. Dostoevsky’s vivid portrayal of the human psyche strongly influenced some of the West’s greatest thinkers—Nietzsche, Freud, and Proust, to name a few—laying the groundwork for much of the psychological, philosophical, and even literary thought that followed.

All this to say: novels have the power to penetrate the public imagination and transform consciousness not only on an individual level, but also on a societal level—and not just in the moment, but across time. Many regard books as fixed in time and meaning, and reading as a passive activity—but the former is outright false, and the validity of the latter is entirely up to the reader. For novels to have a serious impact on one’s life, one must take novel-reading seriously.

a brief note about the history of the novel

Today, much of the panic around reading focuses on its decline. There are endless headlines about the literacy crisis and the decreasing rates of reading for pleasure, plus the backlash faced by Vitalik Buterin and Sam Bankman-Fried for questioning the benefits of long-form reading. For the most part, reading is considered a virtuous activity—good for the brain, a remedy for short attention spans, and a more respectable pastime than scrolling or watching TV.

But this was not always the case. In her fascinating paper The Novel-Reading Panic in 18th-Century in England, sociologist Ana Vogrinčič argues that moral panic about novel-reading began to take shape in England3 at the time, targeted primarily at women for fear that it would corrupt them.

One of many examples, here’s an excerpt from a 1796 essay:

Women, of every age, of every condition, contract and retain a taste for novels . . . [T]he depravity is universal. My sight is every-where offended by these foolish, yet dangerous, books. I find them on the toilette of fashion, and in the work-bag of the sempstress; in the hands of the lady, who lounges on the sofa, and of the lady, who sits at the counter. From the mistresses of nobles they descend to the mistresses of snuff-shops – from the belles who read them in town, to the chits who spell them in the country. I have actually seen mothers, in miserable garrets, crying for the imaginary distress of an heroine, while their children were crying for bread: and the mistress of a family losing hours over a novel in the parlour, while her maids, in emulation of the example, were similarly employed in the kitchen. I have seen a scullion-wench with a dishclout in one hand, and a novel in the other, sobbing o’er the sorrows of Julia, or a Jemima.

During this period, the novel was defined as a proper literary genre but was not widely respected. Unlike the traditional, lengthy heroic romances that depicted, in lofty poetic language, aristocratic heroes fighting for big causes in faraway settings, the novel focused on representing, in simple and colloquial terms, the everyday lives of everyday people from the middle and lower classes. The novel took on familiar settings, made contemporary references, and detailed the inner life; this created a certain level of intimacy between the reader, hero, and author. Concerns around novel-reading varied. They could produce “dangerous psychological affects, triggering imitation and inoculating wrong ideas of love and life,” or they could be “a physically harmful waste of time, damaging not only the mind and the morale of readers, but also their eyesight and posture.”

Women—who were the primary leisurely readers and also considered more sensitive and susceptible to bad influences—might read a fictionalized yet realistic storyline and come to expect certain things out of life. Articles about women ruining their lives due to novels proliferated. Literary reviews were often hostile, not to individual titles but to the genre as a whole: “What we have said of the generality of our Novels, for these fifteen years past, will serve for this one. It is just as pert, as dull, and as lewd as the rest of the tribe.” Authors and readers alike rejected the term “novel” due to the stigma around it (perhaps similar to people rejecting the term “creator” when it first emerged?); readers would find ways to hide their reading.

Circulating libraries were compared to brothels and gin-shops, while readers were considered superficial, lazy, incapable of serious study, negligent, careless, and emotional. Novel readers were thought to read only for the plot, skipping chapters, rushing to the end, and making excessive sentimental notations. This 18th-century stereotype of novel readers is, thankfully, foreign to us today; on the contrary, reading is often seen as the antidote to so many of society’s current ailments.

In a 1789 letter addressed to the editor of The Gentleman’s Magazine, one man writes:

Novels have been long and frequently regarded not as being merely useless to society, but even as pernicious, from the very indifferent morality, and ridiculous way of thinking, which they almost generally inculcate. Why then, in the name of the common sense, should such an useless and pernicious commodity, with which we are over-run, go duty-free, wile the really useful necessary of life is taxed to the utmost extent? A tax on books of this description only (for books of real utility should ever be circulated free as air) would bring in a very considerable sum for the service of Government, without being levied on the poor or the industrious.

In a 1778 essay titled On Novel-Reading, Vicesimus Knox writes:

If, however, Novels are to be prohibited, in what, it will be asked, can the young mind employ itself during the hours of necessary leisure? To this it may be answered, that when the sweetened poison is removed, plain and wholesome food will always be relished. The growing mind will crave nourishment, and will gladly seek it in true histories, written in a pleasing and easy style, on purpose for its use.

If it be true that the present age is more corrupt than the preceding, the great multiplication of novels has probably contributed to its degeneracy.

Imagine any of this being said about novels today! The very attributes of the novel that caused panic hundreds of years ago are celebrated today for connecting us with humanity: universal depictions of real life, everyday people as heroes, glimpses into inner lives and individual psychologies.

We’ve come a long way in recognizing novels as the art form they truly are, capable of changing our lives and the world for the better.

Some people will argue that the process is not magical, but I refuse to accept that. Creation is part magic. Do not argue with me!

Incidentally, in a recent YouTube video, Malissa (@bewareofpity) talks about quitting a book she didn’t enjoy and then feeling bad because there were so few reviews of it online. The way she talks about this book makes it seem human—living: “That made me feel bad. I started feeling like this book was sentient and had feelings and, once again, had been neglected by another reader—by me. So, I do want to finish this book and potentially put out another review of it into the world.”

Vogrinčič focuses on 18th-century England because of the circumstances at the time that enabled the popularization of novel-reading:

Literacy rates in England were increasing, partly because of the Puritan influence on laypeople to individually read the Bible. England’s parliamentary system of government also played a role in promoting literacy by stimulating a news culture for society to engage in state decision-making.

A functioning book market, driven by England’s capitalist economy.

The industrial and commercial revolution in England helped the publishing business thrive, but it also separated the public (work) from the private (home), giving importance to the concept of spatial and psychological privacy, where something like novel-reading for leisure can develop. Since women were more likely to be bound to the home, they tended to make up most of the reading population.

Your writing is so fun to read. You put words to the thoughts I struggle to articulate. I wholeheartedly echo your point on how the right novel at the right time can change your life. I've felt something similar with well-written television (emphasis on well-written). Watching a show from the 2000s sometimes feels like time travel. Tony Gilroy (an extremely talented screenwriter) once described movies as short stories and television shows as 1500-page novels. I see a lot of interesting parallels between how we view television today and how the 18th century viewed novels. I wonder what people will be writing about television three centuries from now :)).